I think Walter Mossberg of the Wall Street Journal might have started the comparison in a very personal article he wrote about the thoughtful and personal side of Steve Jobs. Rick Newman at US News and World Report picked up on the theme but threw mostly cold water on the comparison of Jobs to either Edison or Ford. Even the Christian Science Monitor got into the act with a followup article to Newman's. At this particular moment in time, the loss of a leader in any field is felt acutely and the loss of someone with as many proven leadership skills as Steve Jobs is perhaps all the more strongly felt amongst the rest of us.

Of course, only history will be able to sort out the contributions of Mr. Jobs. But it seems safe to at least question some of the aspersions that Rick Newman made in his piece. Mr. Newman writes of Edison:

By the late 1800s, Thomas Edison developed an electric-lighting system that literally turned darkness to light and ushered in sweeping second- and third-order changes, from the improvement of working conditions in factories everywhere to safer homes no longer lit by candles.

Thomas Edison was a persistent, egocentric, dynamic leader of highly skilled technologists whom he employed to help create his vision for new products. (Sounds kind of like Steve Jobs to me.) He never pursued anything without thinking about its likely commercial impact. He was a master of managing his image in the media. His work on the incandescent light was innovative not because he found a filament that could endure long durations of being heated, but because he envisioned that to make lighting successful he would have to build the whole system. This included the dynamos, the distribution wiring, the switching, and the end appliance - the electric light. That he pulled it off was a testament to his determination and persistence in the face of many, many hurdles.

Having said that, Edison didn't get it right when it came to extending his vision. He defended his direct current (DC) approach in the face of Tesla's clearly better alternative of alternating current (AC). AC power could be distributed without losses over much greater distances than could DC power. Edison even went so far as to mount a public relations campaign against AC power as being much more dangerous than DC. To prove his point, he was instrumental in the development of the electric chair for executing criminals. In the end, it took another generation of innovators beyond Edison and Tesla to make commercial lighting a reality for most people. Samuel Insull, who made commercial electricity a reality in Chicago, was the first of many of these innovators who built large electric distribution systems to bring power to the people.

Edison didn't get candles out of the home. Most people in the late 19th century were lighting there homes with either piped in gas or with kerosene. Factories were often lit by simply more windows or if night work was required, lighting was provided by arc lamps which predated Edison's invention of the lightbulb.

So who gets the credit? Edison for the first embodiment of an electric lighting system or Tesla or Insull? The answer is, of course, all of them, not just Edison alone. If Edison hadn't developed his system, someone else would have done it within the next five to ten years. It was the focus of too many innovators who wanted to be first to show the new power of electricity.

Henry Ford is a different case but he also shares many similarities to Steve Jobs. Ford was neither a particularly talented machinist or even all that literate. What he did have in spades was the ability to envision a new type of automobile and the charisma and passion which attracted really good engineers to work with him to make it a reality. His first focus was not on a car for the masses but on racing cars (which were the earliest means of demonstrating automotive technology and reliability). He was a partial-founder of two automobile companies that failed to achieve his vision. It was only when he decided to be the founder of his own company - where he controlled the vision - that he began to succeed.

His first cars were not particularly different from scores of other startup auto companies. Everyone was selling to a customer who had the means to spend several thousand dollars on a car. Ford's genius was to see that if the cost of the car could be reduced dramatically, a mass market could emerge for the automobile for the first time. Ford not only hired great engineers, he hired a great business manager, James Cousins, to manage the finances of his company. Ford didn't invent the assembly line. That idea emerged from his engineers touring the disassembly lines of the Chicago meat packing plants. Ford provided the single-minded focus to pursue the dream of a mass market car when everyone else told him he was crazy. The result was the introduction of the Model T in 1908 (This was not his first model. There had already been Models A through S before the T came along).

Ford was a true innovator. He was the first to recognize the value of vertical integration in the automotive industry - owning everything from the iron mines to the steel mills to the final assembly plants in the giant River Rouge complex. Ford pioneered the five dollar day for his workers - not just to have them earn enough money to be able to afford a Model T but to get them to not quit (employee turnover on those first assembly lines was in the hundreds of percents). Ford's vision proved to be correct and his company dominated the industry. But unlike Steve Jobs, Henry Ford did not die young. He lived long enough to have his initial vision become an impediment to Ford Motor Company's future. He would not give up on the Model T even when it was outdated and sales were plummeting. He micromanaged his son, Edsel's, period of running the company after Henry ostensibly retired. It would take Ford's grandson, Henry II, to put the company back on track.

So the traits that seem to recur in these three men of different eras and different industries are incredible vision, an awe-inspiring sense of determination, dictatorial decision-making, charisma, passion, and an ability to hire the best and the brightest and give them the environment to create. Each had the ability to see a future, not a future that others couldn't see, but a future which was holistic - one that went further than just one product to see what was needed to make it valuable to millions of people.

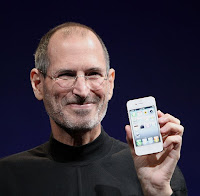

So in defense of Steve Jobs, I think he will, indeed, go down in history as being in the same league as Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and a host of other visionaries who have helped to create the world we live in. His legacy will be felt for generations in the digital devices that are the offspring of the iPods, iPhones, and iPads. His legacy will be felt in the digital animation studios that come after Pixar. His sense of what the market needed was truly remarkable. But even more remarkable was his willingness to bet the company on his vision - not once but over and over again. Steve Jobs was the quintessential American Innovator. Even though I never met the man, I will miss him.

(Disclaimer: I have been a longtime user of Apple products. I am typing this on my iMac desktop computer.)

1 comment:

Even though I never met the man, I will miss him.

Me too. And many others feel the same way-- I just walked by an Apple Store in London today where a crowd was gathered around a makeshift memorial out front: flowers, notes, and (of course) many apples.

I think you're right to put Steve in the same league as Edison and Ford, and the historical context is interesting. His influence is already felt far beyond Apple products (Windows, after all, took most of its cues from MacOS). It's remarkable that he changed personal computing not once, but several times over.

Post a Comment